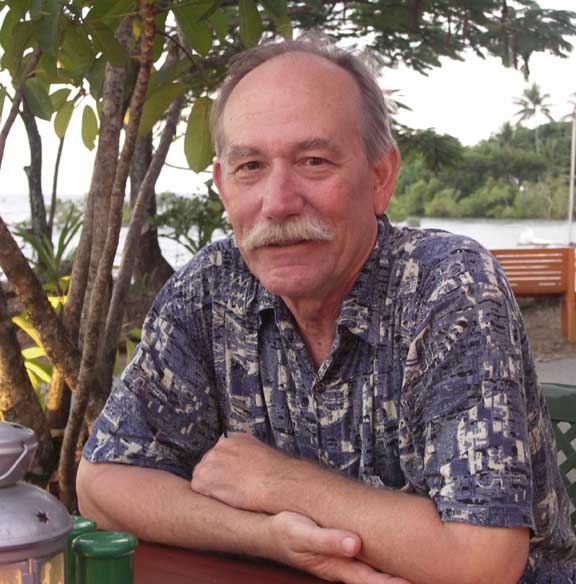

In Memoriam

Thomas Harold Loy, 1942 — 2005

Dr. Tom Loy, molecular archaeologist, was born in Los Angeles, California

in February, 1942 and died at his home in Brisbane Australia in October

2005 of natural causes. At the time of his death, he was a Senior

Lecturer in the School of Social Science, University of Queensland, Brisbane,

Australia. His research interests included hominid tool use at Pliocene/Early

Pleistocene cave sites in South Africa, tools of the Italo/Austrian Ice Man

Mummy (Ötzi), and theory and logic in archaeology.

A memorial service for Tom was held November 7th at the University of Queensland.

Click here for a PDF

of the Memorial Program (Back/Front), or Memorial

Program, Inside.

This site was created and is maintained by his brother, Dr. Gareth Loy, as a personal homage.

Contributions from others are welcome.

A Biography

Early Life

Thomas Harold Loy was born in 1942 in Los Angeles, USA. His father, Harold

Amos Loy, was a fourth generation Methodist minister. His mother, Maxine,

was the daughter of Thomas Max Reitz, a Kansas farmer. All T. Max

Reitz's sons became Ph.Ds in agriculture. Maxine, an accomplished

singer and pianist, received a BA in music. When Tom was born, W.W.II

was underway. Our parents were strong advocates of what was called

in those days the Social Gospel. They were pacifists, and marched

against the war in the streets of Los Angeles. When Japanese Americans were

sent off to internment camps, our parents helped care for their property

until they could return. When the Japanese Americans were finally

released at the end of the war, Harold preached from his pulpit that they

should be welcomed back to the community as loyal Americans. Some

in the congregation stood up and walked out. During the 1950's, black

Americans were struggling for equality and freedom in the US. In response,

Maxine and Harold developed a program of Black (Negro) Spirituals, which

they performed in churches in Southern California, teaching racial tolerance

to white audiences.

When they moved to Glendale Arizona in the late 1940's Harold and Maxine

carried their social ministry to the native Navajo peoples in that area.

Tom became friends with the Navajo children. Tom strongly identified

with the Navajo, and from then on his life was devoted to understanding indigenous

people of the world, and their cultures.

Tom loved the out-of-doors. Our family was poor, so our vacations

were mostly camping trips to the Mojave Desert or backpacking in the Sierras.

Tom and Dad found a Pleistocene horse jawbone, dinosaur bones, trilobites,

and many kinds of semiprecious gems. Tom became a proficient outdoorsman

through the Boy Scouts, able to live in the wilderness on his own for weeks

on end by age 16.

Upon graduation from Chino High School in 1959, he attended Redlands University.

He was strongly influenced by the Beat poetry movement in San Francisco,

and and became a fine poet himself (see his poem

below). He once rode a Lambretta motor scooter 500 miles to San

Francisco to attend poetry readings at City Lights Bookstore and to see trumpeter

Miles Davis at the Hungry I. He graduated with a B.Sc. (Geology) from

Redlands University in 1964.

He served his country in the Army Reserve. Afterwards, he moved to

Alaska, taking a job as a cartographer for United States Geological Survey,

later working on an oil rig, and prospecting. He routinely went prospecting

for months at a time in the Arctic outback, looking mostly for nickel. He

told fascinating stories of his adventures with blizzards, bears, moose,

and near starvation when he missed a supply drop from a bush pilot. (He said

he killed an old goat to survive until the next drop.) He loved the

roughneck culture of Alaska, and enjoyed playing washtub bass with the Glacier

Valley Boys at the Double Muskie restaurant and bar. He eventually

completed an MA (Anthropology/Archaeology), from the University of British

Columbia. He performed Field work in the Frazier River Valley, Muncho Lake,

and in Yoho Park in the Canadian Rockies. Tom could read the earth like an

open book. His facility with living off the land gave him an uncanny ability

to identify archeological sites and find fossil remains. His focus

was always on the people who had used the artifacts he found.

Blood from a Stone

About this time, Tom made a discovery that was to propel him into the forefront

of science and establish his world class reputation. He was personally responsible

for the creation of an entire sub discipline of archaeological research

known as residue analysis.

In 1981, while working for the British Columbia Provincial Museum, he became

curious about the organic residues on the surface of the stone tools he'd

been excavating. The received analytical wisdom of the time was that this

was just dirt to be washed off before curating the artifacts. Tom asked

the elementary question: what was this material? Tom used the new

electron microscope at his museum to photograph the residue of an unwashed

obsidian arrow point at high magnification. A medical scientist colleague

of his confirmed that the residue included red blood cells preserved on

the face of the artifact. The discovery site of the arrowhead was thousands

of years old, which meant that the residue was that old as well.

This raised many questions: how could the proteins on the artifact survive

intact for a millennium? What kind of animal's blood was this? If its type

could be determined, a new window would be opened into the hunting habits

of ancient indigenous peoples worldwide. Was this preservation common, or

a fluke? In what circumstances and over what ages could such residues be

found? His answers to these questions led to the publication of his famous

paper (Science 1983). His work

struck a chord in the public imagination. Numerous newspaper articles talked

about the scientist who could extract blood from a stone. There is no doubt

that Tom was the world pioneer in this field. And there is no doubt that

being a pioneer is risky and dangerous in science. His theories were angrily

challenged by some, and his work came under suspicion even in the court of

public opinion. In the mid 1980's, the Museum administration proved

that it had no spine for the controversy by firing him from his position

on trumped-up charges.

But he shortly received an opportunity to continue his research in Australia

via an appointment to Australian National University, Canberra. He was able

to refine his research methods, teach, and finish his Ph.D. With the

help of his colleagues, the thesis of his Science article was eventually

vindicated, and he gained an international reputation for his work, with

publications in such journals as Antiquity (see References). Later, he accepted a position at UQ

in Brisbane where he lived and worked until his death.

Ötzi

As an indication of his high esteem, he was invited by the authorities

in Innsbruck, Austria to help investigate Ötzi the Iceman, arguably

the prehistoric archeological find of the last century. Tom studied Ötzi's

tools, clothes, and other artifact residues, and later helped establish

the Iceman’s cause of death. To be a member of such a select team of scientists

reflected well not only on Tom, but also on the scientific establishment

in Australia that provided him with a home for his research for over 20 years.

Passing

As he was nearing retirement, he was also beginning to wear out physically.

He suffered all his life from a hereditary blood deficiency. He complained

of headaches and feeling faint. He was not well. He consulted a doctor,

took medical leave that was due to him, and planned to go to Camooweal,

site of much of his recent research, to open an archeological field school

there. Because he chose to conduct research in such far-flung places in

the world, he was out of reach of family and friends for long stretches

of time. He always had a suitcase with clean clothes ready to fly

off on his next adventure, which you'd typically hear about only when he

got back. He never made it to Camooweal, but died in his house. He

is survived by his children, Curtis, Inge, Kim, Adam, Max, and Emma.

Tom had a deep appreciation for the ephemeral nature of his human existence,

as illustrated in his poem "Los Serranos," excerpted below. The setting

of the poem is the mist shrouded rolling hills of his home in Chino, California

where he and his father occasionally played golf together.

Los Serranos (excerpt)

Out of the mists of an early summer dawn

when the coolness of the air promises a hot afternoon

ghost gums float in the gray-green sea of grass

and the night smells are only just gone

two figures, father and son, walk some distance apart

up a long incline, guided by a small flag

The memory of the flight of our small white balls pull us over the hills

where once, banditos and their silver horses jingled through the same

mists of summer –

Stealing time, pulling us through the hole in the past opened by the morning:

Each strike of the ball is an unrecoverable unit of time,

time reduced to just that moment

the last shot forgotten, the next awaiting in the galactic unreachable

future.

And they, the father and the son, leave behind only the worm tracks of

balls rolling in the dew

and footprints leading into the mist.

Selected References

- Loy, Thomas H. June 1983.

"Prehistoric blood residues: detection on tool surfaces and identification

of species of origin." Science, 220(17):1269-1271.

- T. H. Loy and B. L. Hardy. "Blood residue analysis

of 90,000-year-old stone tools from Tabun Cave, Israel." Antiquity,

66(250): 24–35.

- Tom's own views of archaeology and links to an audio interview with

Tom talking about Otzi is on the web. Go to http://www.archaeologyweek.com

then click on the "Meet the Archaeologists". Scroll down to Tom's name (entries

are ordered alphabetically by surname) and click on "dig deeper".

Home Pages